Food Labels Reveal the Value in a Name

What’s in a name?

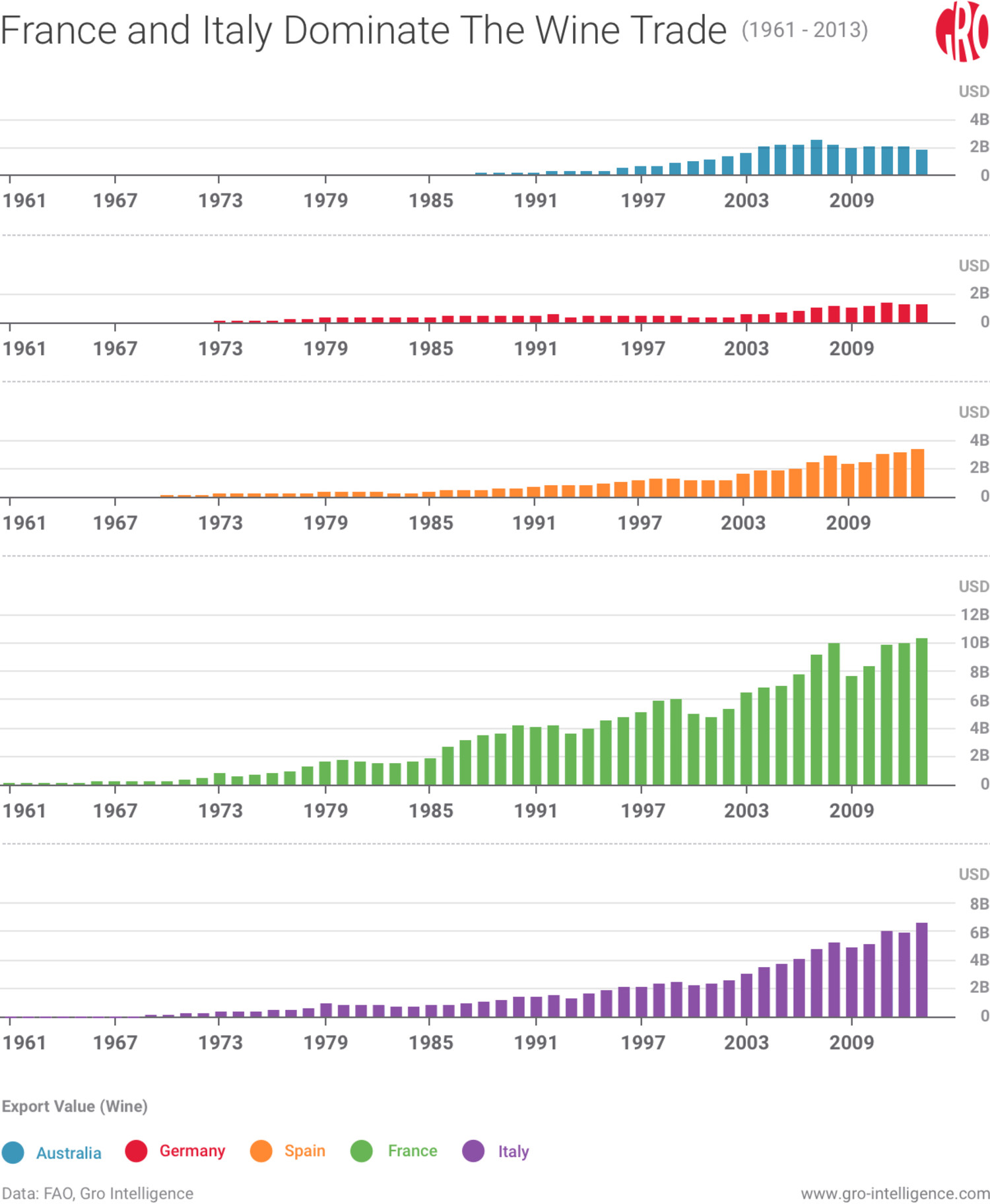

Italy only needs to look to its neighbor France to understand the value in a label. Champagne has become synonymous with sparkling wine, but only wines grown in the Champagne region of France can legally use the name. The Treaty of Madrid in 1891 established these rules and winemakers from the region have benefited ever since. France exported $10.3 billion worth of wine in 2013. Half of that value was in champagne shipments. In 2016, 33,805 French hectares were dedicated to the production of 268 million bottles of champagne worth 4.7 billion euros.

Champagne’s status includes strong protections against brand infringement or market confusion. Champagne, Switzerland lost its battle to use the town’s name on products as part of a deal that allowed Swissair to make stopover flights in EU cities.

Discount supermarket chain Aldi also learned the power in that name. Aldi released a champagne sorbet as part of a 2012 holiday campaign. Champagne producers objected swiftly even though the sorbet contained authentic champagne. The European Court of Justice ruled in Big Champagne’s favor and the final verdict on the case will be decided in a German court in the near future.

Over time, a Made in Italy label might carry the same status as champagne or become as ubiquitous as McDonald’s golden arches or Coke. There’s a clear monetary value to a name that resonates with consumers. Brand equity is the premium placed on the consumer’s perception of a name regardless of its quality or uniqueness in the market. Coca-Cola, as a company, had a revenue of $41.9 billion in 2016. As a brand, Coca-Cola was estimated to be worth $73.1 billion.

Italy has a broad range of products that could benefit greatly from the new label. While monetary gain is among the benefits of this proposal, Italy states better differentiation from cheaper competition is even more important.

A pizza the pie

Italy is the seventh largest exporter in the world having exported $448 billion in goods in 2015. Cars were the top Italian export with a value of $22.8 billion. Crude petroleum ($22.7 billion), petroleum gas ($16.2 billion), and packaged medicine ($14.1 billion) were also among the top Italian exports in terms of value.

Driven by wine, pasta, baked goods, chocolate, and processed tomatoes, foodstuffs had an export value of $23.9 billion. Italian wine had an export value of $6.3 billion in 2015 with the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Canada as the top destinations. Pasta accounted for $2.63 billion while baked goods had a value of $1.92 billion. The foodstuffs category does not include the $2.47 billion brought in from cheese exports or the additional $1.67 billion from pure olive oil exports.

The Italian agricultural industry argues its top exports are threatened by recent European Union resolutions that have increased trade from Africa and Asia. The EU and Vietnam agreed in 2015 to lift almost all tariffs beginning in late 2017. Italy is the EU’s top rice producer accounting for 51 percent of all production. Vietnam has yet to gain a foothold in the EU, but the availability of cheap imports is putting a strain on prices. Cambodia is also benefitting from the EU free trade agreement and France is the second-largest importer of Cambodian rice behind China. Italian fruits and vegetables are also at a competitive disadvantage from these favorable trade deals, according to Coldiretti, Italy’s agricultural association.

Consumer confidence is another rationale for a Made in Italy label. A poll conducted by the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry stated that 85 percent of the 26,000 citizens surveyed were in favor of transparency.

Italy passed an origin label law for dairy products in 2016 with a similar goal of protecting farmers and increasing consumer transparency. It rapidly became apparent that nearly half of all mozzarella made in Italy was produced using imported milk. This hurt the Made in Italy brand by making consumers feel deceived, according to Coldiretti. The majority of Italians were in favor of knowing the country of origin for ingredients in dairy products and cheeses. Those surveyed were willing to pay up to a 20 percent premium for Italian products.

Italy’s plan to create country of origin labels for its pasta became a controversial topic outside of the EU when Canadian wheat exporters expressed concerns over the system. With a key market at stake, a label could negatively impact prices and reduce trade.

Food fight

Italians led the world by consuming 33.5 pounds of pasta per capita in 2016. On an absolute basis, Russia and Brazil are the top pasta eating countries at 1.22 million tonnes and 1.18 million tonnes, respectively. On that scale, Italy trails in third place.

Italy is the top importer of Canadian durum wheat. This type of wheat has a high level of protein, which improves its elasticity and suitability for use as a primary ingredient in pastas and baked goods. Since Italian farmers produced just under four million tonnes of durum wheat in 2014, millers needed to import over a million tonnes from Canada in order to meet consumer demand.

Many have called the Italian decree a protectionist ploy to promote the Italian brand to consumers. Coldiretti cites food safety concerns stemming from the usage of the pesticide glyphosate, which they claim may be carcinogenic. Food labels created to promote food safety have had little success in recent years. The rationale for regulators’ hostility to such labels becomes clear in a 2004 case from the US beef industry.

At the 2004 height of the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or “mad cow”) panic, one small beef producer got an education in the heavy control the USDA and FDA maintain over domestic food labeling. Japanese importers had demanded that Creekstone Farms certify that all of their meat had been tested for BSE before it would be accepted for import. The producer complied with the requirement. Seeing potential for a new revenue stream, Creekstone Farms wanted to begin testing all of their beef, putting the test result on their labels, and selling it in the US at a premium.

The USDA emphatically said “no.” They asserted that the US beef supply was safe and that USDA certification must suffice for US consumers to feel secure. US meat did prove to be safe, and as far as we know, no human BSE cases ever arose as a result of the US beef industry.

Over the years, a number of labels in addition to mandatory US grading (Prime, Choice, and Select) have entered the picture, such as “organic”, “no antibiotics”, and “no hormones”, but none of them explicitly refer to short-term food safety. Some consumers may believe that hormone-treated beef will harm their health, but no one seriously thinks that it will kill them right away. An unsafe food system will certainly harm people’s health immediately. The USDA and FDA jealously guard their deservedly good reputations for preventing foodborne disease in the US. They have the legal power to deny market participants the ability to freely label their products.

Most recently, the World Trade Organization ruled against the United States in a country of origin label (COOL) dispute involving Canada and Mexico. The US wanted to require beef and pork products to have origin labels. Canada and Mexico objected to the mandate, claiming that it would create a competitive imbalance between the countries. The WTO agreed, ruling that the US label mandate violated trade obligations. The US complied, repealing the COOL law in 2015.

Conclusion

Italy’s label decree has plenty of fans and detractors. Italian farmers support the proposed system while millers are less thrilled about it. Pasta makers rely on wheat imports to meet domestic demand. The new labels may lead to more products made exclusively from Italian wheat, like Barilla’s Voiello brand. But Italy’s wheat crop won’t grow enough to supply 100 percent of Italy’s millers. Therefore consumers will decide the new policy’s success with their wallets when they choose entirely domestic or partly imported products.

The recent spat further highlights protectionist policies as reactions to free trade agreements. Canada and the EU signed the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) in 2016, which would eliminate virtually all tariffs if the agreement is enacted in 2019. CETA would make Canadian durum wheat even cheaper and leave Italian producers at a severe disadvantage.

For something so small as a label, Italy’s decree highlights the many colliding forces involved in food. From the local level to the international stage, governments are promoting policies that serve their narrow interests. What’s best for the Italians may hurt Brussels and vice versa. Industries are also at odds in these decisions as processors want policies that reduce manufacturing costs while farm associations want more money for farmers.

Food labels have succeeded when centered on perceived notions of quality, but labels based on safety have failed to gain approval. There’s already consumer support for a quality label and Italy should continue to focus on better transparency for the long-term success of a “Made in Italy” brand.

Insight

InsightLow US Hard Red Winter Wheat Production Likely, Despite Acreage Boost

Insight

InsightChina’s Grain Imports Reach Record With a Growing Reliance on Brazil

Insight

InsightUS Soybean Acreage to Shrink to a Four-Year Low, Gro Predicts

Insight

Insight

Search

Search