How Kenya Can Work Its Way out of a Food Crisis

Drought fits La Niña pattern

While the current food crisis in Kenya seemed to strike suddenly beginning in April of this year, there were warning signs very early on that a drought would hit East Africa. Gro published a blog post on the drought in early March indicating that soils and crops across the region had severely low moisture content, a sign that harvests would not be strong. To start, 2015-16 was a very strong El Niño year, which is often followed by La Niña years typically bringing a much milder short rainy season in October to December.

El Niño and La Niña are opposite phases of a weather pattern called the El Niño Southern Oscillation, in which fluctuations in sea-surface temperature in the equatorial Pacific cause global weather patterns to shift temporarily. In October 2016, warnings were issued that Kenya’s short rains could start later and end earlier, causing yields for staple crops such as maize to decline by as much as 50 percent in some parts of the country. In that scenario, wholesale prices of maize would rise, and processors would be forced to import maize to make up the local production deficit. This is the scenario that ultimately played out.

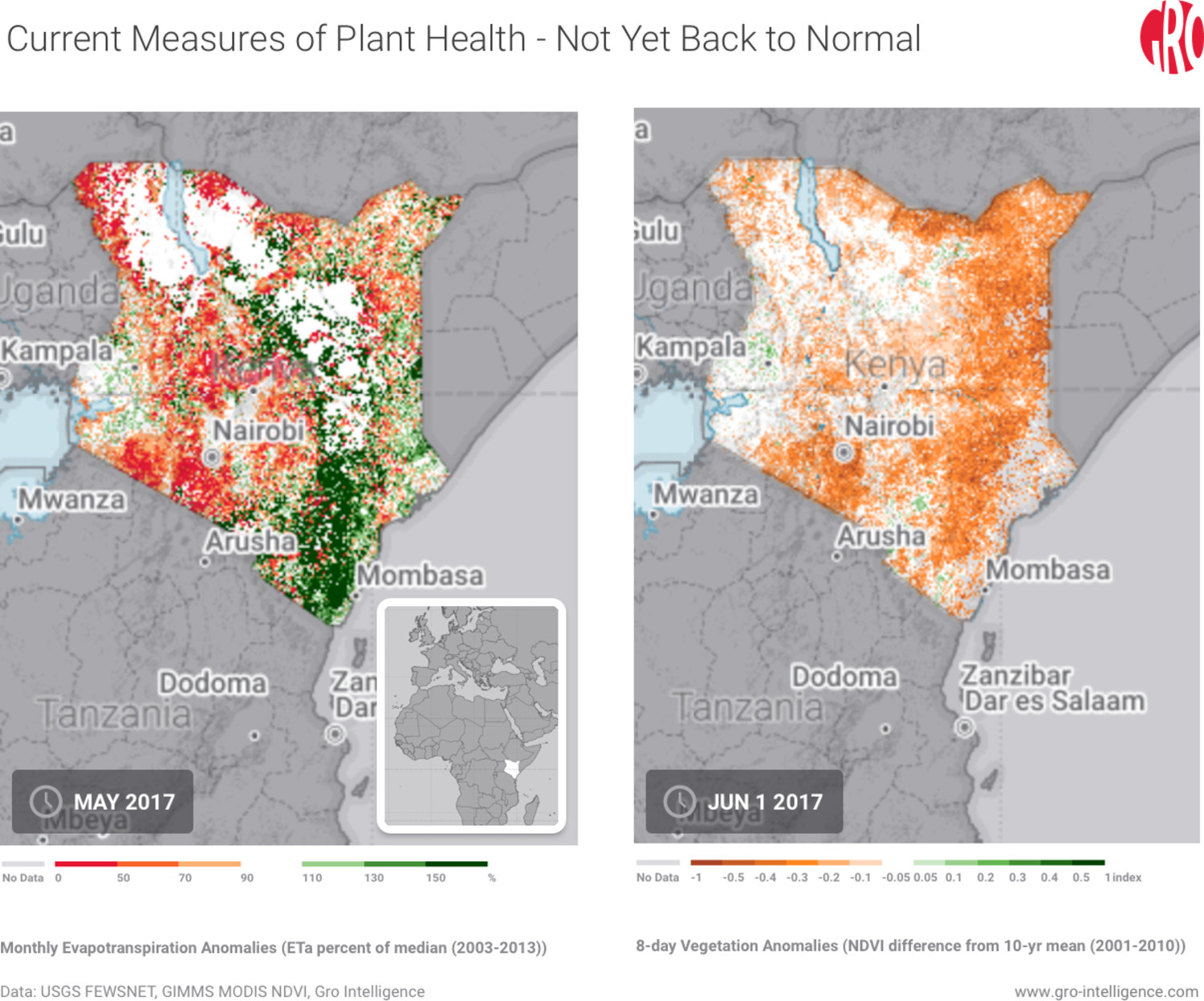

Rainfall across Kenya was far below normal from October to December 2016, leading to drought conditions across most of the country. By January, Kenya was looking parched along with most of Eastern Africa, including Tanzania, which is Kenya’s largest maize trading partner. Nevertheless, the government said it had no plan to import additional maize to support the country’s farmers, because stocks of other food would hold out.

Drought leads to inflation

As prices for food staples started to rise after the sparse rains of late 2016, the government slowly began to respond. In January, exports of maize were banned to keep available stocks within Kenya, as there was concern that Kenyan farmers might hold out for higher prices from export markets. But the price of maize kept rising because Kenya has been a net importer of maize for the past 10 years.

Starting in February, maize stocks held in the national strategic grain reserve by the National Cereals and Produce Board (NCPB) were released onto the market and sold to millers. Each release of additional maize onto the market provided some relief to rising prices that was often short-lived. Then in April, the government removed import tariffs on maize, which are typically set at 50 percent. Due to delays caused by logistical constraints, this wouldn’t have an effect on maize supplies for weeks or months.

By May 15, the NCPB had released all but half a day’s supply of maize from the strategic grain reserve, to no avail. In May, the price of wholesale maize had risen 14.5 percent above its price in April, and 54.3 percent above its price from May 2016. Finally, with no more market-based recourse, the government decided to try more direct intervention. A 6-billion-shilling (close to $60 million) subsidy program was rolled out, which would cover close to half of the cost of maize that processors paid. Processors would then be obligated to pass the cost savings on to retailers and consumers, and maize flour would sell for a fixed price of 90 shillings (about $0.87) per two-kilogram packet. Since the subsidy was rolled out, the government has promised another 3.7 billion shillings (about $36 million) to replenish the depleted strategic grain reserve.

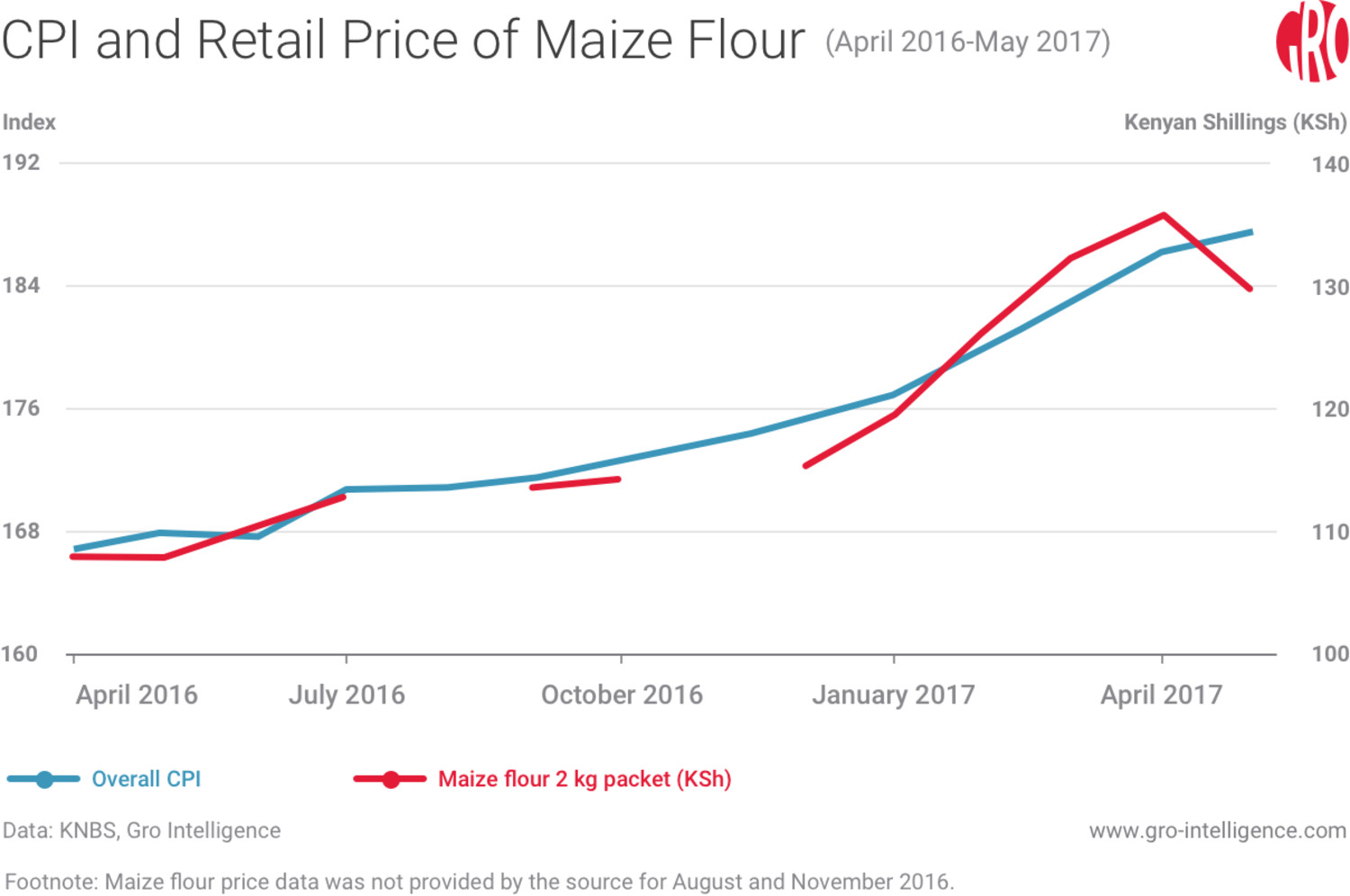

But by that time inflation had already started to get out of hand. The retail price of maize flour rose 31.3 percent year-over-year in April and fell 4.6 percent in May only as a result of the government subsidy. In May, the price of sugar was 49.4 percent above its price a year earlier, and packeted milk prices had risen 22.7 percent in a year. The higher prices of these agricultural staples pushed the consumer price index (CPI) 11.7 percent above its value a year earlier. By comparison, the difference from May 2015 to May 2016 was only 5 percent.

A better information infrastructure would have facilitated a more timely reaction from policy professionals. Heading into the La Niña season, there were already forecasts that considerably less rain would fall during the short rainy season in late 2016, threatening some areas of the country with food scarcity.

On the plus side, the country had a strong buffer against this kind of catastrophe in the form of a strategic grain reserve that can hold 5 million 90-kilogram bags (450,000 metric tons, or close to two months of Kenya’s maize consumption). But by mid-May the reserve was nearly empty after the government released only 1.05 million bags, suggesting that it wasn’t fully stocked. If there was a time for the government to buy maize, that time should have been in late 2016 in order to fill up the strategic grain reserve, once it was clear that the short rainy season was below average. Purchasing 3.95 million bags in December would have cost about $160 million. The funds that have currently been allocated ($60 million for the subsidy and $36 million promised to replenish the reserve) could have bought 2.37 million bags, close to a full month’s supply for the entire country.

Kenya not out of the trouble zone

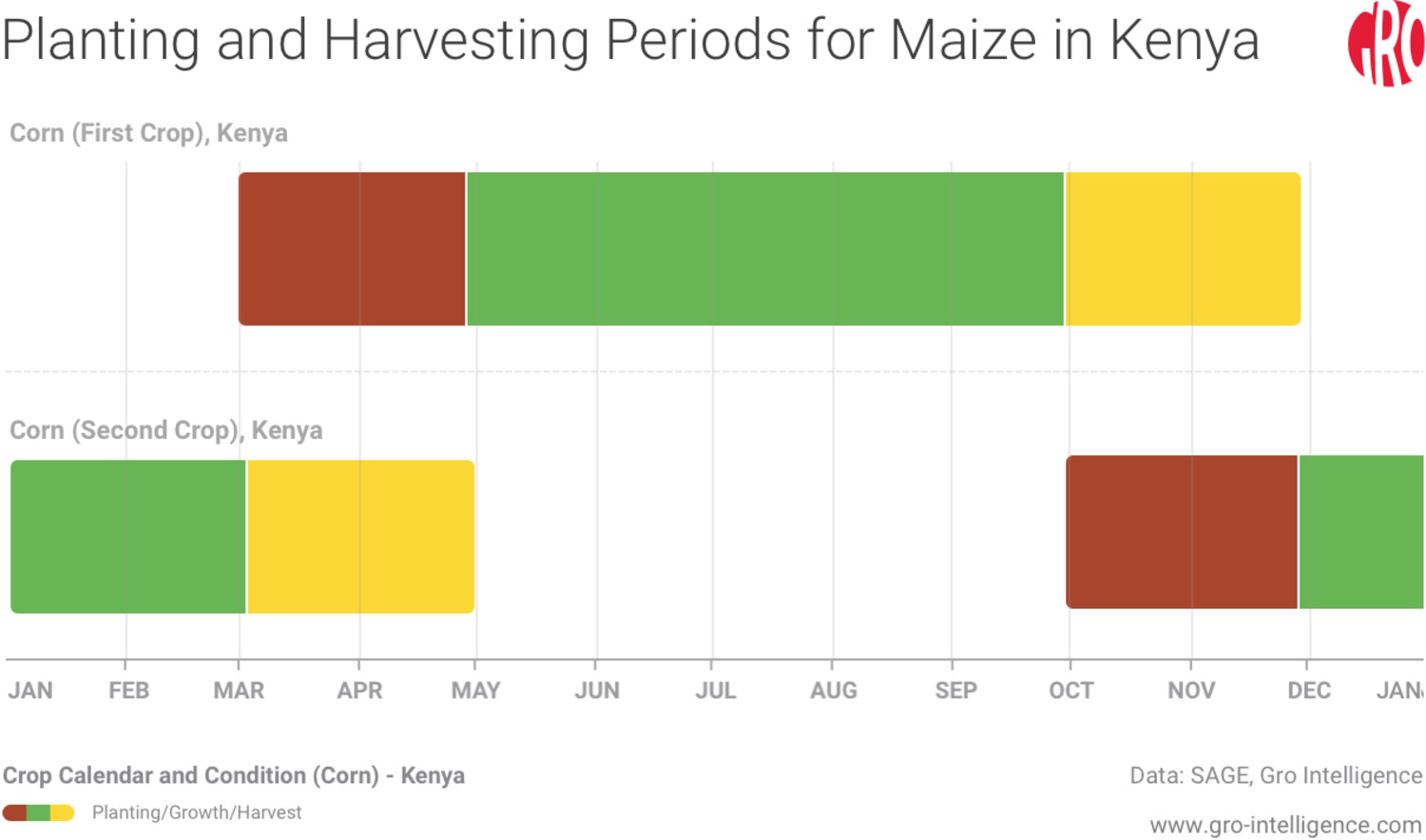

Kenya is now in the growing season for its larger maize crop, which means that the need for live monitoring is greater than ever. Furthermore, it’s now the maize growing season in the US, which produces 38 percent of the world’s maize.

Monitoring conditions in the US is critical. Gro’s initial yield model estimates indicate that this year’s maize yields in the US will be well below trend, with our latest forecast at 156.74 bushels/acre (9.84 metric tons/hectare), 10.2 percent below 2016’s yield. If yields this low materialize, maize prices should rally significantly from currently near five-year lows. The implications for global prices would be large, with serious knock-on effects on maize prices in Kenya. Domestic prices are largely a function of domestic conditions, but the global supply and demand balance also has a big impact. The world’s maize markets watch the US crop intently through the season. They know how important it is.

With the drought still affecting Eastern Africa and a likely low maize yield in the US, Kenya isn’t out of the woods yet. Policymakers still need to be prepared, and the strategic grain reserves still need to be filled.

Conclusion

In late 2016, drought hit much of East Africa after the La Niña-induced reduction in rainfall. The short rainy season in Kenya, which runs from October to December, was shorter and drier than normal, leading to lower output of maize during that growing season. In early 2017, as the drought continued, a shortage of staple foods began to show itself. Maize flour in particular, one of Kenya’s most important staples, was in short supply, and prices began to rise as stocks diminished. Eventually, higher food prices bled over to the rest of the economy, with the total inflation (measured by year-over-year increase of the CPI) climbing to 11.7 percent in May 2017, up from 5.0 percent in the same month a year earlier.

Policymakers attempted a few interventions to contain the steep price inflation, including banning maize exports, removing import tariffs, and releasing strategic maize reserves onto the market. Despite these efforts, inflation persisted. Eventually the administration introduced a subsidy to the wholesale price of maize under the condition that any flour produced would be sold at a low, fixed cost to consumers.

These measures have had some success in the short term, but the longer term problem remains. Early warnings of drought should quickly empower officials to replenish strategic reserves and reduce tariffs. Such immediate actions can head off a potential crisis before it begins without the need for expensive and market-distorting subsidies. But Kenya will need to improve its data infrastructure to pursue a proactive policy like this one.

Furthermore, it’s not certain that the recent crisis has fully ended. Local prices remain too high, and any crop problems in the US or other major markets could lead to renewed anxiety for Kenyan consumers. Giving the professionals in charge of the country’s food policy at all levels a clear view of agricultural developments worldwide would be a welcome first step toward mitigating the remainder of this crisis and preventing the next one altogether.

Blog

BlogSouth America: Fall Planting Snapshot

Insight

InsightTexas Cotton Prospects Wither as Extreme Heat Continues

Insight

InsightMorocco’s Drought-Imperiled Wheat Crop Points to Untimely Import Pressure

Insight

Insight

Search

Search