Mexico Trade Barriers Will Raise US Food Prices, but What of Quality?

Background

The present-day Mexican economy bears little resemblance to that of twenty years ago. Between 1994 and 2016, exports of goods and services jumped from 13.3 percent to 38.2 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), while total trade simultaneously surged from 29.3 percent to 78.1 percent. Fueled by its burgeoning export economy, Mexico’s GDP per capita in purchasing power parity (PPP) has risen from 8,000 to nearly 18,000 international dollars over the same period, according to the World Bank. Global auditing giant PricewaterhouseCoopers predicted that Mexico’s economy will further climb to the ninth largest in the world by 2030 (in PPP), ahead of both France and the United Kingdom, and the sixth largest by 2050.

In 2016, 81 percent of Mexico’s total exports and just under 80 percent of its agricultural exports went to the US. Accounting for $13.2 billion USD in 2016, fruit and vegetable products were by far the most valuable category of Mexican exports to the US (using the World Customs Organization’s HS Code groups). Tomatoes ($2.06 billion), avocados ($1.83 billion), peppers ($1.13 billion), raspberries and blackberries ($854 million), tree nuts ($561 million), strawberries ($556 million), cucumbers and gherkins ($510 million), lemons and limes ($434 million), and grapes ($408 million), nearly all in their fresh forms, represented the largest by value.

Mexico’s export-fueled economic growth has coincided with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Yet NAFTA has also had its faults. Relative to American and Mexican politicians’ ambitions for the deal, both economic growth and wages in Mexico have remained subdued. Although the Mexican economy has grown, the magnitude of the change is far less than most experts predicted. Meanwhile, poverty levels are roughly the same and unemployment has actually risen in Mexico since NAFTA.

So far commercial growers and food processors have been the biggest winners in Mexico, which now ranks among the 15 world leaders in agribusiness according to the US Department of Commerce. Despite vast mountainous terrain, 55 percent of Mexico’s land is classified as agricultural area compared with 44 percent in the US, according to the FAO. Benefiting from diverse climates and low production costs, Mexican agricultural production has flourished in tandem with increased demand from the north.

The Mexican government has also done its part to assist the country’s export industry. Most notably, Mexico invested five percent of its GDP into infrastructure in 2010. Between its 85 airports, 26,700 kilometers of railroad, 366,000 kilometers of road, and 76 seaports spanning 11,000 kilometers of coastline on two oceans, Mexico is quickly becoming one of the most “interconnected” countries in the hemisphere.

Of the primary Mexican agriculture exports to the US, many are already grown by US farmers.

With reduced tariffs and a more fluid flow of goods across the northern border, Mexico’s agriculture has slowly reoriented itself as a mere agricultural extension of the southwestern United States. With close proximity to the US, Mexico is the primary provider of fresh fruits and vegetables during many US winter months. Now, with potential US trade barriers on the horizon, Mexico’s largest agricultural exports may not fill American shelves as cheaply.

When it comes to feeding the US, it takes a hemisphere

Several of Mexico’s largest agriculture exports clearly display this mismatch between demand and supply.

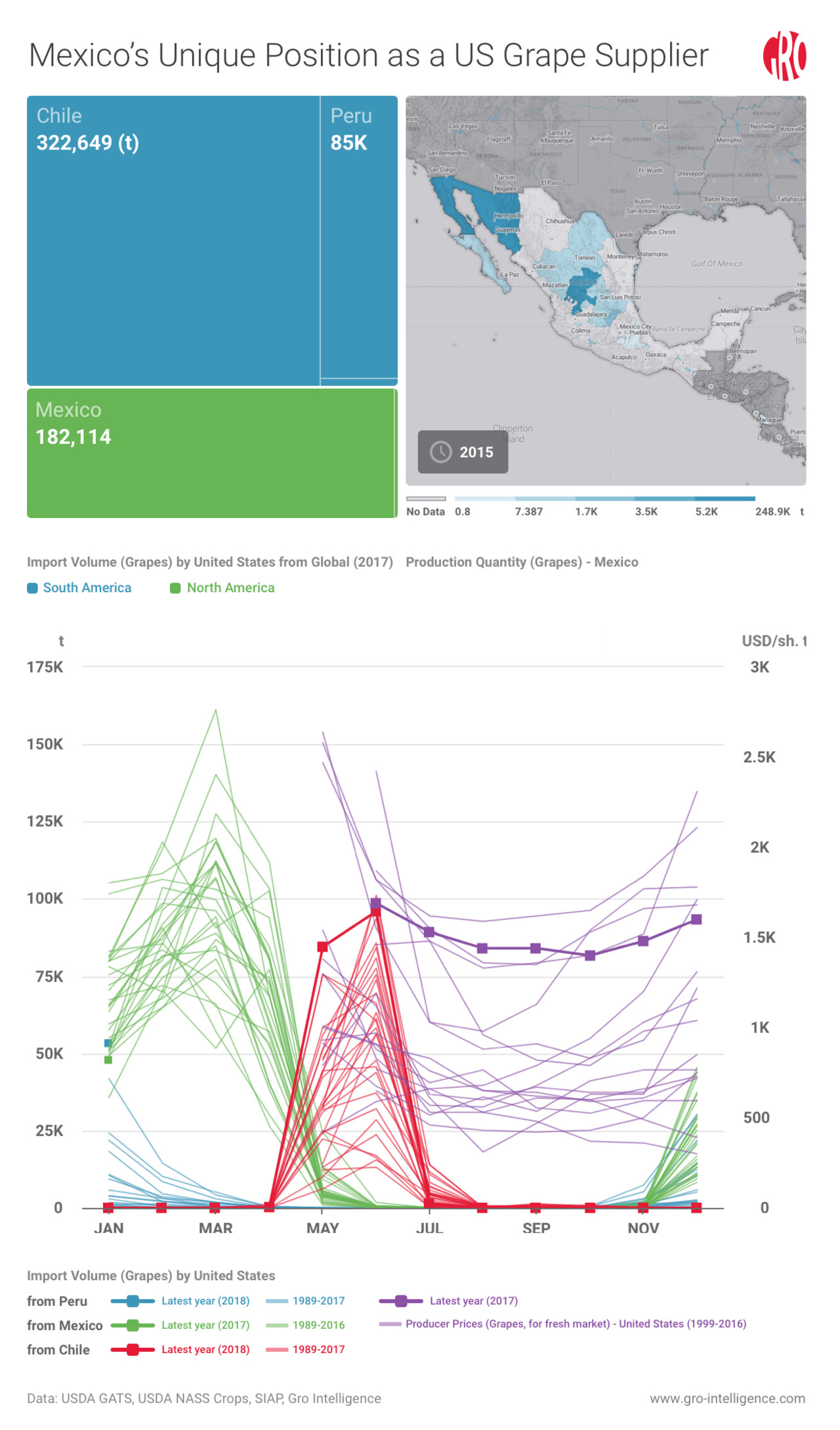

The United States, for example, has been a net importer of grapes since 1982 despite its significant history with the fruit. The US state most associated with grapes, California, still produces the lion’s share of the country’s crop—roughly six million tonnes annually. Yet the US imported 290 thousand tonnes of grapes in 2017.

Monthly export data depicts how California and Mexico’s agricultural production cycles often form a complementary relationship. Burgeoning fruit and vegetable producers, Chile and Peru, significantly bolster the US fresh grape supply during their respective summers. In the spring, vineyards in the US often need a few more months of warm temperatures before harvests can begin in June. So, Mexico’s northwestern Sonora State, which is topologically similar to southern California, provides the majority of the US fresh grape supply in the interim.

Just when it seemed like avocados couldn’t get any more popular in the US, they did. Americans went from consuming 2.2 pounds of avocados per capita in 2000 to 7.1 pounds in 2016, according to the USDA.The Hass avocado—by far the fruit’s most popular variety—was developed in the United States, but domestic demand in recent years quickly outpaced US production. Thus, the US imports avocados from Mexico year round. Like grapes, the US will also bolster its off-season avocado supplies with imports from Mexico and other southern countries.

Native to Mesoamerica, avocados grow best in more moderate heat and humidity. Southwestern states, such as Michoacan, are responsible for the majority of Mexico’s avocado output and are the primary suppliers of the US market. Additionally, avocados do not adhere to traditional growing seasons. Abnormally cool temperatures can induce alternate bearing cycles in avocado trees, affecting yields from year to year. Significantly further from the equator than most other growing regions, California’s avocado yields are highly variable and can present significant risk to both US prices and supplies without support from Mexican avocado imports.

Not every major produce export from Mexico to the United States is necessarily of a tropical variety. Native to western South America, tomatoes are capable of growing in a wide range of climates. During the Northern Hemisphere’s summer, when tomatoes can be grown en masse without the use of greenhouses or other inherently restrictive technologies, Canada is able to produce enough tomatoes to help meet the demand of its southern neighbor. In other words, NAFTA has allowed the US market to utilize arable land across the entire continent in order to satiate its demand for tomatoes. Since 1994, US tomato imports from Canada rose from 7.6 to 165.4 thousand tonnes, while imports from Mexico have risen from 376 thousand tonnes to 1.6 million tonnes.

Looking forward

Mexico and its farmers often provide cheap and highly-demanded produce north of the border during seasons when no other country is fully capable.

The removal of trade barriers is massively beneficial to consumers but not necessarily to producers. Especially with commodities that can and have been grown consistently in both countries, farmers are wont to engage in trade disputes that often escalate to the level of national politics.

Yet US President Donald Trump’s protectionist outbursts have so far been directed toward Mexican manufacturing rather than its farmers. Given the recent US tariffs on steel and aluminum, President Trump may be attempting to deliver on campaign promises by circumventing and renegotiating NAFTA rather than scrapping it altogether. On the other hand, the departure of the Trump cabinet’s primary economic advisor and free trade advocate Gary Cohn indicates that the struggle over the fate of NAFTA may have only just begun

Potential scenarios and defenses

Assuming that the current administration does ultimately decide to disrupt the status quo, US procurement teams can prepare in a few ways. First and most imminently, areas of the Southwest US that require costly irrigation to become arable may now become attractive investments to domestic growers looking for higher quality produce during the early spring or late fall. Meanwhile, farms already in operation will see the value of their land skyrocket. Purchasing land in advance could help mitigate the risks of NAFTA renegotiation.

Second, Caribbean fruit and vegetable exporters like the Dominican Republic could make new efforts to increase production and compete for newly vulnerable market share in the US. Occupying similar latitudes as most of Mexico, many Caribbean islands are unusually well positioned to ship fresh fruits and vegetables to the nearby US market. Quickly locking in deals with those farmers will also be essential as most Caribbean countries are strictly limited by a relative dearth of cropland.

Third, and looking much further ahead, high-density vertical and indoor farming ventures might begin to become more viable. Consumers looking for produce of any quality during the winter will still be able to rely on imports from South America, but Mexican exports will become more expensive. That will give indoor farming operations additional leeway to target the consumers who are willing to pay a premium for higher quality, locally sourced winter produce

Lastly, large food and beverage companies might even devote additional research and development funding to more efficient means of shipping fruits and vegetables long distances. Ultimately, however, in the short term US consumers will probably simply spend more on the same produce from Mexico.

Alternatively, the United States could grow enough of any one crop currently imported from Mexico to make up for potential shortfalls. US fruit and vegetable farmers will naturally reconsider which crops to sow in light of new supply and demand dynamics. However, it is unlikely that price increases will significantly diminish demand and spur supply enough to rid the US of its Mexican produce habit. Thus, avocado, tomato, and other large-scale produce imports will continue.

NAFTA renegotiation will cause less suffering for Mexico’s farmers and agribusinesses than one might instinctively assume. Mexico has the second highest number of free trade agreements of any country in the world, so revisions to NAFTA can be partially mitigated by the others. This commercial network extends to 43 countries located on three different continents. Given the aforementioned infrastructure investments, agribusinesses within the country are well prepared to compete with countries such as Peru and Chile who also rely on export markets abroad. Mexico also recently signed onto the (American-less) Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, which will open their agriculture exports to roughly 400 million new people. Despite the new trade bloc being even larger than the US market, no deal can offer the geographic proximity of NAFTA.

In most post-NAFTA scenarios, the US does not have other sourcing options that are immediately ready and able to replace the convenience, quality, and scale of Mexican produce. Moreover, Mexico can clearly compete in other markets, so the biggest losers in a NAFTA-less world would appear to be American produce consumers.

Insight

InsightFor Super Bowl Savings, Serve Wings and Guac - and Skip the Veggie Platter

Insight

InsightExtreme Weather Is Fueling Produce Prices and US Food Price Inflation

Insight

InsightExpect High Tomato Prices in Hurricane Ian’s Wake

Insight

Insight

Search

Search