Mexico and US Craft a Sweet Deal for Some

Background

The Mexican and US landscapes for sugar cultivation differ greatly. In one of the country’s primary agricultural activities, 150,000 Mexican sugarcane growers directly or indirectly employ roughly 2 million people. Sugarcane plots in Mexico average roughly four hectares (10 acres) in size. In stark contrast, the United States has just over 600 sugarcane growers cultivating on average plot of 500 hectares (1,236 acres). The US also has 4,000 sugar beet farms with an average size measuring 130 hectares (320 acres).

Both countries’ sugar policies march to similar protectionist beats. The US has collected protective tariffs on foreign sugar imports since the dawn of the Republic. The US has liberalized its trade relationship with Mexico following NAFTA. Despite WTO obligations, the country tightly controls supply from other countries by setting trade restricted quotas—or the amount of imports qualifying for low or zero duties.

The USDA allocates a share of the estimated US sugar market to domestic producers. In theory, this should prevent market oversupply. US sugar growers also receive loans that guarantee a minimum producer price regardless of actual market conditions. These measures work to ensure that US raw and refined sugar prices are generally higher than the world reference price, much to the detriment of confectionary companies. While the US generously protects its sugar industry, neglected food and beverage companies have moved operations elsewhere in search of cheaper sweeteners.

Within Mexico, current sugar subsidies come largely in the form of direct price support. The Decretos cañeros, a government act that was intended to attract foreign investment to the sector, established set reference prices for sugarcane, which the government revises periodically to reflect market conditions. However, domestic control over the industry has fluctuated since the 1970s when the government nationalized the country’s sugar mills. More recently, the Mexican government has increasingly divested its direct involvement in the industry, which is comprised of less than 60 mills.

Over 80 percent of Mexico’s sugar output comes from nine states spread across its Gulf and Pacific coastal regions. In the United States, production of sugar is split roughly 55/45 between beet and cane cultivation. Sugar beets are grown in 14 states, but more than 50 percent of annual production comes from just Minnesota and North Dakota. Likewise, sugarcane production is heavily concentrated in Florida and Louisiana, which account for well over 90 percent of US production.

With the exception of the 2012/13 season, Mexico’s raw sugar output has remained around 6 million metric tons (tonnes) even after the country received unfettered access to the US market in January 2008. Sugarcane yields still remain below global standards in many parts of Mexico. In fact, Mexico’s growers harvested roughly 69 tons of sugarcane per hectare (t/ha) in 2016 compared to 78.5 t/ha for US growers and nearly 75 t/ha for Brazilian producers. However, the country has the potential to produce more higher-quality sugarcane, particularly in the Jalisco, Morelos, Puebla, and Chiapas regions.

On the other hand, US sugar production has steadily climbed between 2008 to 2017 in response to a 15 percent increase in domestic demand. While Mexico’s total demand for sugar has held steady over the same time period, the country’s tax on sugary drinks is clearly impacting consumption. Soda sales were down 5.5 percent in 2014 and 9.7 percent in 2015, respectively.

NAFTA made sweeteners a fungible commodity

Prior to 2008, Mexico’s imports of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) from the United States and US exports of sugar to Mexico were limited and fluctuated significantly. The removal of all quota and tariff restrictions immediately transformed cross-border trade flows. Mexican sugar not only became a competitive substitute to US-cultivated sugar, but also took share from HFCS in the US. HFCS as a percentage of US sweetener supply averaged 39 percent between 2012 and 2014, down from 44 percent in between 2004 and 2006. Mexican sugar became relatively more cost-efficient as rising corn use in ethanol production inflated corn prices. At the same time, public debate over the health impact of HFCS resulted in food and beverage manufacturers replacing HFCS with sugar.

Since the United States consumes most, if not all, of its annual sugar production, rising domestic demand of sugar called for more imports. Mexican exports of sugar to the United States roughly doubled between 2008 and 2014. The new trade regime worked so handsomely in Mexico’s favor that enterprising middlemen would import raw sugar from other global markets and re-export it to the US.

US corn syrup producers also benefited greatly from NAFTA. Many Mexican bottling companies found US corn syrup to be cheaper and more reliable than domestic sources. Exports of HFCS to Mexico quickly picked up steam. HFCS increased from 9 percent of Mexican sweetener use between 2005 and 2007 to roughly 25 percent between 2012 and 2014.

Entrenched interests stop the music

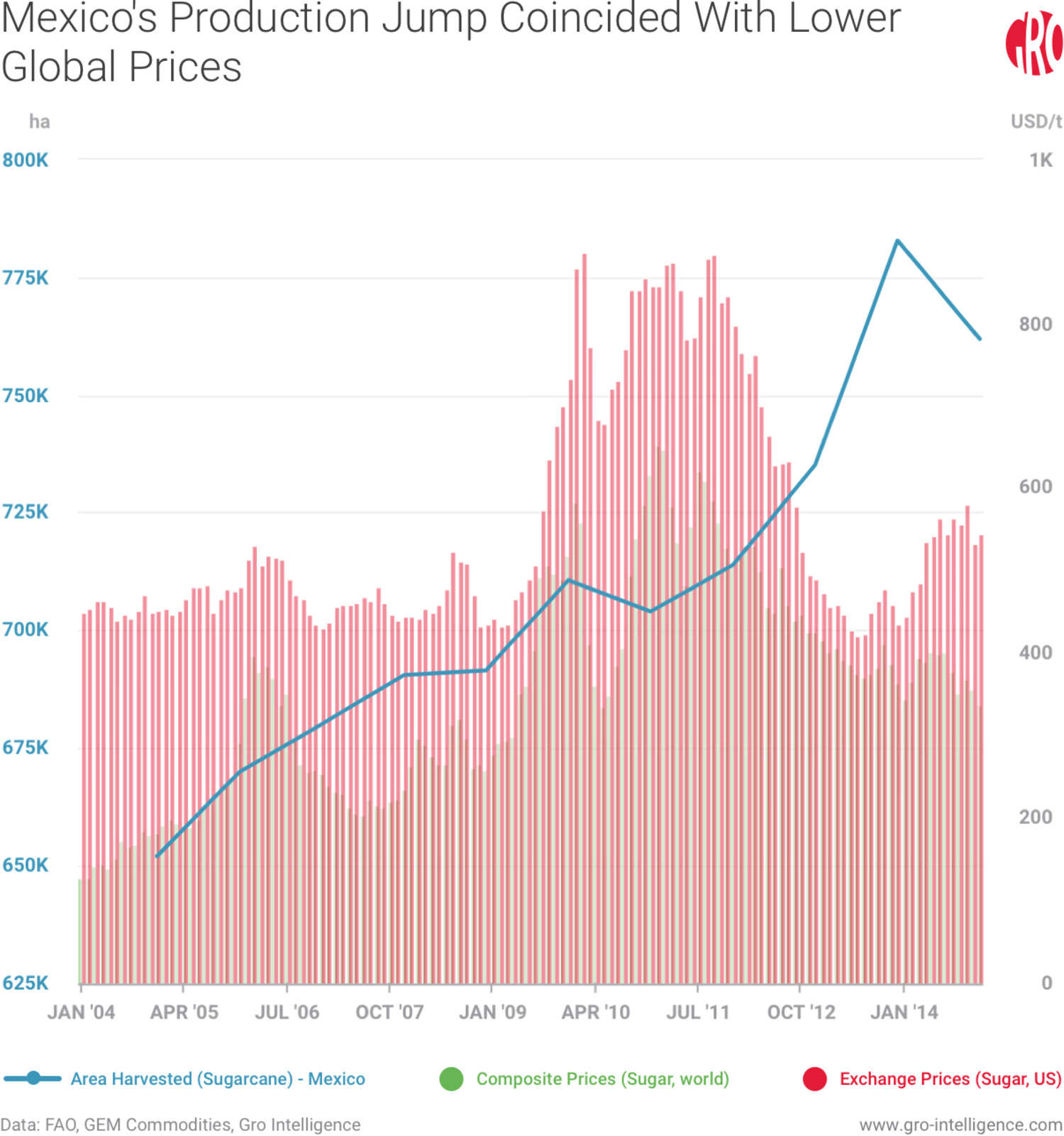

The harmonious balance of rising sweetener trade between Mexico and US ended in 2013. A jump in sugarcane area in Mexico coincided with a tighter spread between US and global sugar prices. As a result, Mexico’s exporters had a greater incentive to export to the US. Total exports of sugar products from Mexico to the US doubled in 2013 from the prior year. Of course, US sugar refineries have no issues with Mexico sending them cheap raw sugar. In fact, the industry has been pushing the US government to expand the quota for raw sugar imports for years. However, growing refined sugar imports to the US caught the attention of the industry.

In an interesting twist, the simultaneous rise in raw and refined sugar imports from Mexico united growers and refiners. The US sugar industry banded together to press for a US International Trade Commission (USITC) ruling against Mexico. Both countries threatened retaliatory measures during the review process.

At the end of the day, both countries agreed to bury the hatchet, as there was too much on the line. They signed a suspension agreement establishing a limit on Mexican sugar exports to the United States. Mexico also agreed to limit refined sugar exports to the US at 53 percent of its total exports. In return, the US set a minimum import price for Mexican refined and raw sugar of 26 and 22.5 cents per pound, respectively. Still, bad blood between the trade partners lingered.

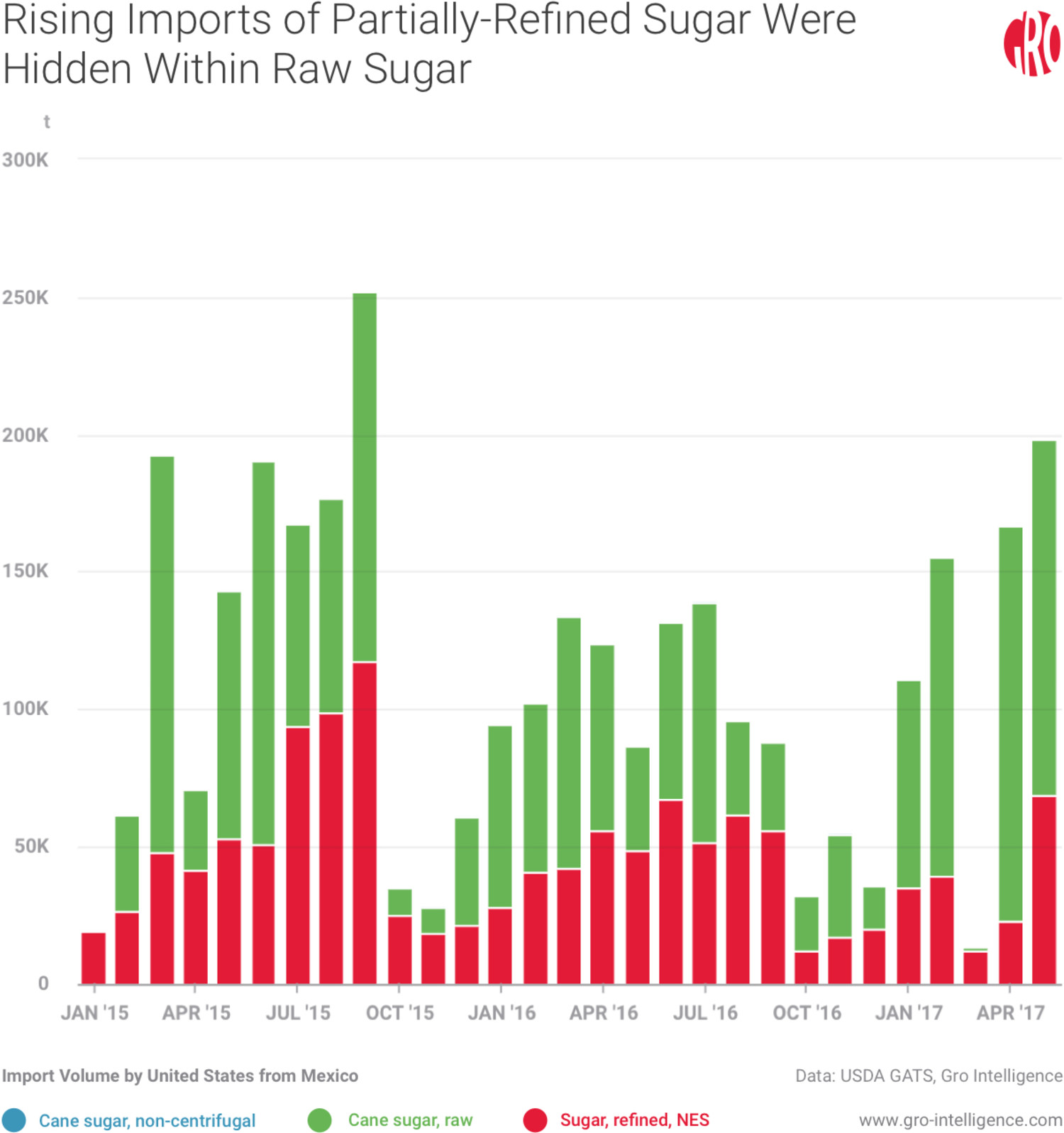

The rise of the melt house

Mexico increased exports to the US of partially-refined sugar, which is technically raw under trade specifications, despite the 2014 agreement. With the country sending less raw cane sugar to the US, US domestic refiners became increasingly dependent on US production and higher-cost imports from other countries via the tariff-rate-quota system.

At the same time, Mexico’s sugar mills and independent players built more “melt house” capacity in the US. Melt houses process partially-refined sugar into liquefied sugar rather than crush and process raw sugar. Liquefied sugar has become increasingly popular among food manufacturers looking for a cheaper sweetener source or a substitute to corn syrup. Under the 2014 ceasefire, Mexico’s exporters were able to export sugar that was technically raw—up to a polarity level of 99.5 percent—but could be easily processed into refined sugar by independent refiners. Indeed, US refiners persuaded the US Department of Commerce to resume investigations into Mexico’s exploitation of this loophole in January 2015. The USITC ruled again in favor of the US sugar industry.

Tensions between the countries ran high ahead of the June 5, 2017 deadline, but disaster was, once again, averted. Mexico agreed to lower the share of its refined sugar imports to the US from 47 percent to 30 percent in return for a roughly 2 cents per pound increase in minimum import prices for refined sugar. Mexico also gained the title of supplier of “first refusal”, which allows the country to supply any extra U.S. sugar demand.

US sugar refineries also won a few key concessions. All raw Mexican sugar will have to be shipped via dry bulk shipping vessels to US ports of destination. The thought is that the availability of Mexican raw sugar will improve for domestic refineries, as most of their legacy operations are located near major port hubs. The polarity limits for raw sugar were also reduced from 99.5 percent to 99.2 percent, which, in theory, should benefit sugar cane refiners at the expense of domestic melt houses.

Still, the US sugar industry has come out against the “grand compromise.” Mexico will be allowed to meet extra US sugar demand under the old polarity definition for raw sugar, which provides a technical loophole. In effect, the industry believes Mexico may end up exporting just as much partially-refined sugar into the US if the USDA calls for extra demand.

Conclusion

While this latest deal will allow NAFTA negotiations to start under calmer circumstances, the root cause of the trade scuffle remains. The United States keeps protecting the margins of sweetener processors at the expense of US consumers and food companies. Despite little evidence of dumping by Mexican exporters, the Mexican government seems most concerned about securing higher import prices and other concessions for Mexico’s growers. The country’s bottling industry isn’t protesting too much over this favoritism. Since Mexico’s bottlers face a domestic deficit, they are happy for the source of tariff-free corn syrup.

Global confectionary companies have largely moved production offshore. They are unlikely to raise a vocal protest during future trade talks unless they are threatened by higher US tariffs. As such, we see politically-connected growers and processors continuing to control US sugar policy. However, US corn processors’ win is pyrrhic at best, with Mexican soda consumption declining and domestic HFCS demand stalled.

Meanwhile, Mexico is trying to even up the score for processors by increasing support for ethanol. Given that the country’s sugar productivity has lagged behind global peers, it is worth asking whether Mexico’s subsidies for cane growers are part of the problem.

All this subsidization is clearly leading to less-than-efficient industries on both sides of the border. Yet politics sometimes trumps logic.

Insight

InsightPoor French Sugar Beet Crop Adds to Global Sugar Inventory Woes

Insight

InsightArgentina’s Wheat Exports to Shrink as La Niña Bites

Insight

InsightIndia’s Sugar Crop on Track for Another Strong Year

Insight

Insight

Search

Search