The Big Egg Challenge: Meeting Demand for Cage Free

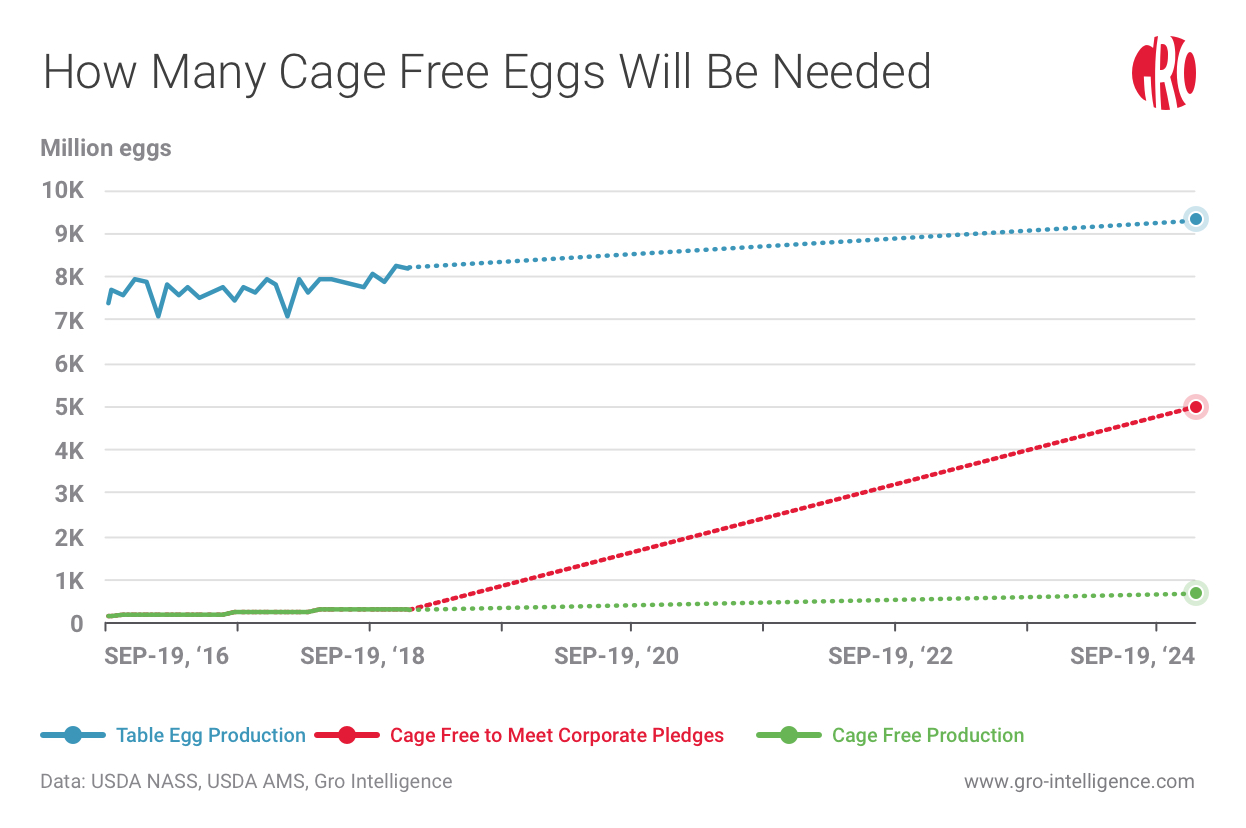

At current growth rates, cage free egg production (green line above) will fall far short of meeting demand from companies that have pledged to only use cage free eggs by 2025 (shown with the dotted red line). The blue line shows a projection of total table egg production based on current growth rates.

Today’s Egg Industry

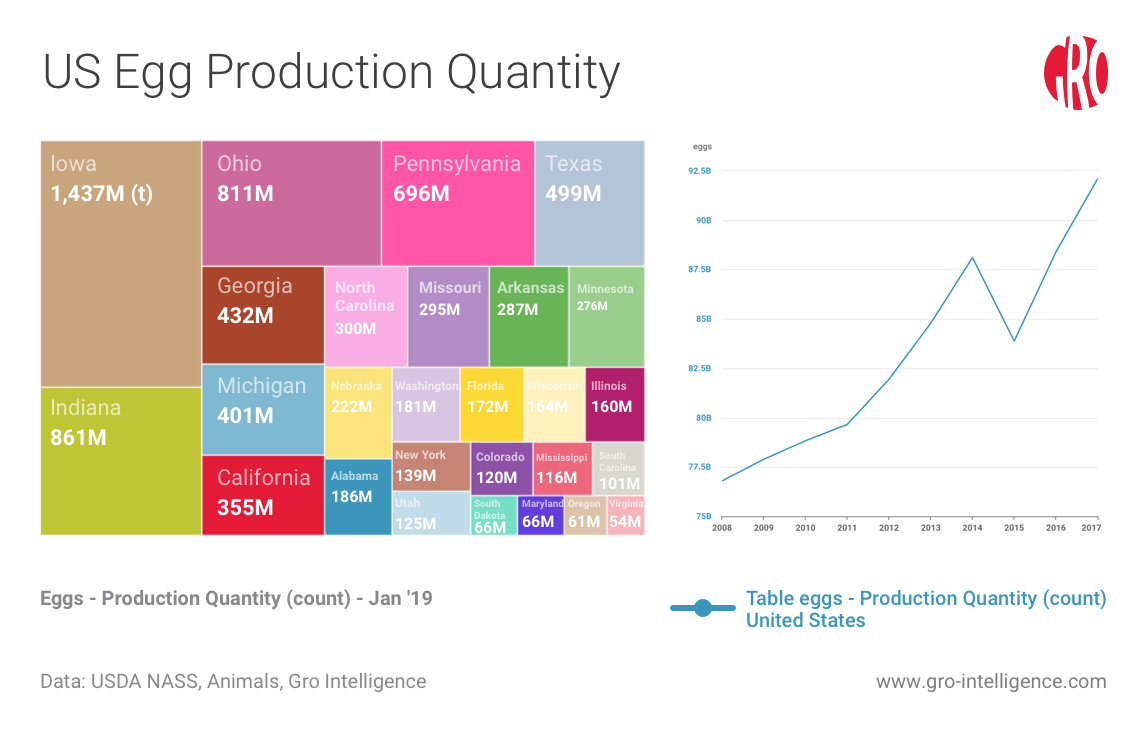

The US produced 92 billion table eggs in 2017, generating sales of $7.55 billion. In 2018, 94 billion eggs were produced and by 2025, production is projected to increase to 112 billion at current industry growth rates. Nearly a third of production goes into what’s known as the breaker channel, meaning it is sold in liquid or dry form to restaurants, bakeries, and food manufacturers. On a per capita basis, Americans consumed on average 279 eggs in 2018, which is up from 248 eggs a decade earlier. (While that sounds like a lot, the US is still well behind countries like Japan, the No. 1 consumer, with 320 eggs consumed per capita.)

Egg production in the US has expanded by 20 percent over the past decade, according to the USDA. That beats out chicken and pork production, both up 10 percent, and beef, down 2 percent, despite the fact those three categories of meat have much higher proportions of production going to export than do eggs.

Conventional eggs make up the bulk of production. Most conventional layers are raised in battery cages that house five to 10 layers apiece. The United Egg Producers, a trade association, calls for a minimum 67 square inches of space per bird. Cages have long been used because they require less space for a layer house. They also reduce the number of broken eggs and the number of layers lost to inter-bird fighting.

To receive a USDA consumer-packaging label of “cage free,” eggs must come from hens that are able to roam vertically and horizontally within an aviary, and have access to scratch areas, perches and nests. The USDA issued its first Cage Free Shell Egg Report in September 2016, providing a monthly focus on the industry.

Other egg categories also have gained ground, including free range, in which chickens are provided access to the outdoors. Organic eggs are produced with similar standards to those of cage free and free range, and are also fed no synthetic amino acids, are restricted in their use of antibiotics, and are fed organic feed in accordance with USDA’s National Organic Program. Some eggs are labeled “natural,” but there is no definition of this in either FDA or USDA regulations.

Third-party verification of animal welfare is provided by a number of organizations, including A Greener World and Humane Farm Animal Care, and is indicated by a label on egg cartons or a symbol on restaurant menus. Common specifications include natural behaviors like perching, dust bathing, running, and wing stretching. Organic eggs are certified by the USDA.

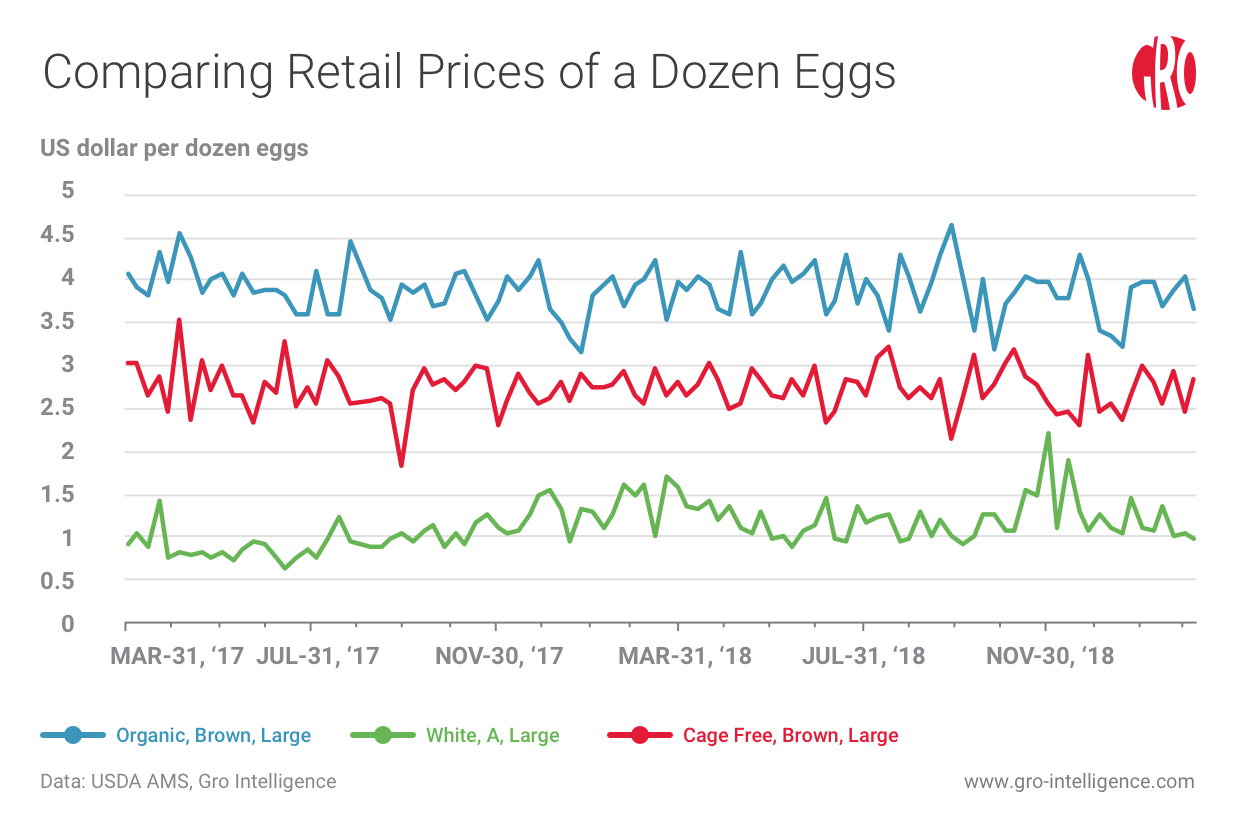

Price-wise, conventional eggs are the cheapest, with an average retail price of 98 cents a dozen nationwide, according to the most recent USDA statistics. Cage free brown eggs average $2.83 a dozen at the retail level, while organic brown eggs retail at $3.67 a dozen.

USDA statistics track average egg retail prices. Organic eggs (blue line) tend to run the most expensive, followed by cage free (red line) and conventional eggs (green line).

Switching to Cage Free

Understanding the differences among categories of eggs for their animal-welfare standards and nutritional value can be confusing to consumers. While there are disagreements about the optimum requirements for animal welfare, the term “cage free” is a readily understandable concept widely associated with humane treatment. For food-service companies, switching to cage free eggs represents a relatively low-cost way to appeal to socially conscious consumers.

Walmart announced its plan in 2016 to transition “to a 100 percent cage-free egg supply chain by 2025” for both Walmart and Sam’s Club stores. The move will “challenge suppliers to use selective breeding practices, innovation and best management practices to improve the health and welfare of laying hens,” said Walmart, which currently sells a variety of eggs, including cage free. The transition is conditioned “on available supply, affordability and customer demand,” it added.

Walmart’s pledge to go fully cage free is similar to public declarations by other companies, including retail giants Kroger and Unilever, and food-service providers like McDonald’s, IHOP, Aramark (which serves schools, hospitals, etc.) and Sysco (the nation’s largest food service provider).

Such corporate pledges to use only cage free eggs add up to a combined 60 billion eggs a year, according to the Farm Bureau, an agricultural advocacy group. If current growth trends continue, total annual table egg production would reach 112 billion eggs by 2025. But cage free egg production would reach only 8.1 billion eggs, assuming current growth rates going forward. That would present a shortfall of nearly 52 billion cage free eggs below the level of demand indicated by the corporate pledges. So, either cage free egg production is going to have to expand much more rapidly in the next few years, or corporations will have to abandon their pledges.

The number of cage free layers in the US (blue line, left axis above) is dwarfed by the total number of table egg layers (red line). But cage free layers have quickly gained as a percentage of the total (green line, right axis).

Price of a Dozen Eggs

For existing egg producers, switching to cage free production requires upfront capital investment to rip out existing cages, build perches and dust-bathing and scratching areas, and, overall, provide layers with more space. Ongoing costs also are greater because of higher mortality rates among free-roaming chickens and an increased rate of egg loss.

Producing a dozen eggs from cage free layers costs about 24 cents more than from layers housed in conventional cages, an increase in cost of production of about 36 percent, according to research conducted by the Coalition for Sustainable Egg Supply. The coalition brought together animal welfare scientists, academic institutions, nongovernmental organizations, egg suppliers, and restaurant/foodservice and food retail companies to evaluate various laying hen housing systems. The researchers, working on a commercial farm in the Midwest, assessed conventional cage, cage free aviary, and enriched colony systems.

In enriched colonies, layers are kept in cages that have double the footprint of conventional cages and provide access to a scratch area, perches, and nest boxes. Production costs in enriched colonies are 9 cents, or 14 percent, higher per dozen than in conventional cage housing, the coalition’s research found. The United Egg Producers and the Humane Society of the US jointly supported US federal legislation introduced in 2012 to make enriched colonies the industry standard, but the legislation failed to pass.

Clearly, many consumers can expect to pay more if the market share of cage free eggs grows to half the total market by 2025, as the combined amount from corporate pledges would suggest. If, for instance, we considered half of today’s egg market to be cage free, and that cage free’s higher production costs were passed along to consumers, then the total annual cost of US eggs would increase by about $1.3 billion, or 18 percent, from current levels. The increase could be even greater, by dint of the fact that cage free eggs’ retail price premium over conventional eggs typically exceeds the 36 percent difference in production costs. On the other hand, production costs for cage free eggs could decrease as the industry expands, putting downward pressure on retail prices.

The chart at right shows the increase in the number of table eggs, which exclude eggs for hatching, produced in the US over the past decade. At left, a breakdown of total egg production by US state.

What’s Ahead

Is such a big shift to cage free eggs achievable? Yes, but consumers may need to be willing to pay more, a behavior that hasn’t often been seen in the marketplace. For their part, consumer-facing companies may have to suffer some short-term profit-margin declines in order to cement a reputation for serving humanely raised products. Restaurants might feel greater pressure to maintain their cage free egg commitments than, say, institutional food service firms, which are generally less transparent about their ingredients. Additionally, the further eggs are processed—in baking, for instance—the more likely their cage free distinction is lost.

Corporate declarations to use only cage free eggs generally included market-based caveats that could allow companies to back away from their pledges. Another possibility is that momentum will build toward using eggs from enriched colonies, which give layers more space than conventional cages but has lower costs of production than cage free.

As it stands today, supply of cage free eggs lags far behind the industry’s projected demand. There is a significant shift toward corporate social responsibility in agribusiness, and within the egg market this shift is focusing on cage free. If either production or consumption doesn’t increase dramatically, the cage free egg market will remain much smaller than corporate purchasers’ pledges currently imply.

Search

Search