Biotech Soybeans in Argentina

Argentina and Biotech

Argentina is responsible for 14 percent of all biotech crops grown in the world, producing more of these crops than any country except the US and Brazil. Virtually 100 percent of Argentina’s cotton and soybeans, and 95 percent of the country’s corn are biotech varieties.

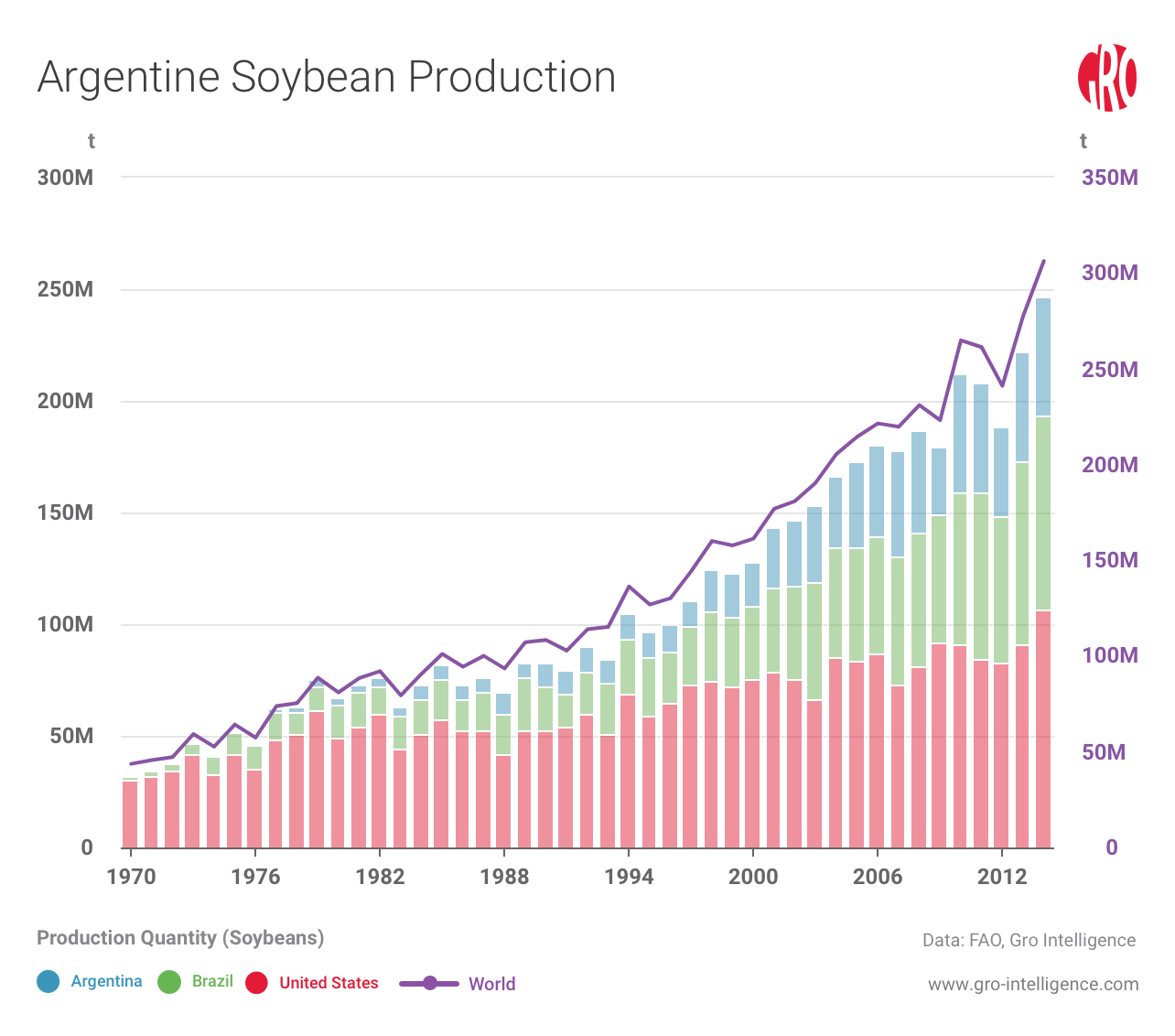

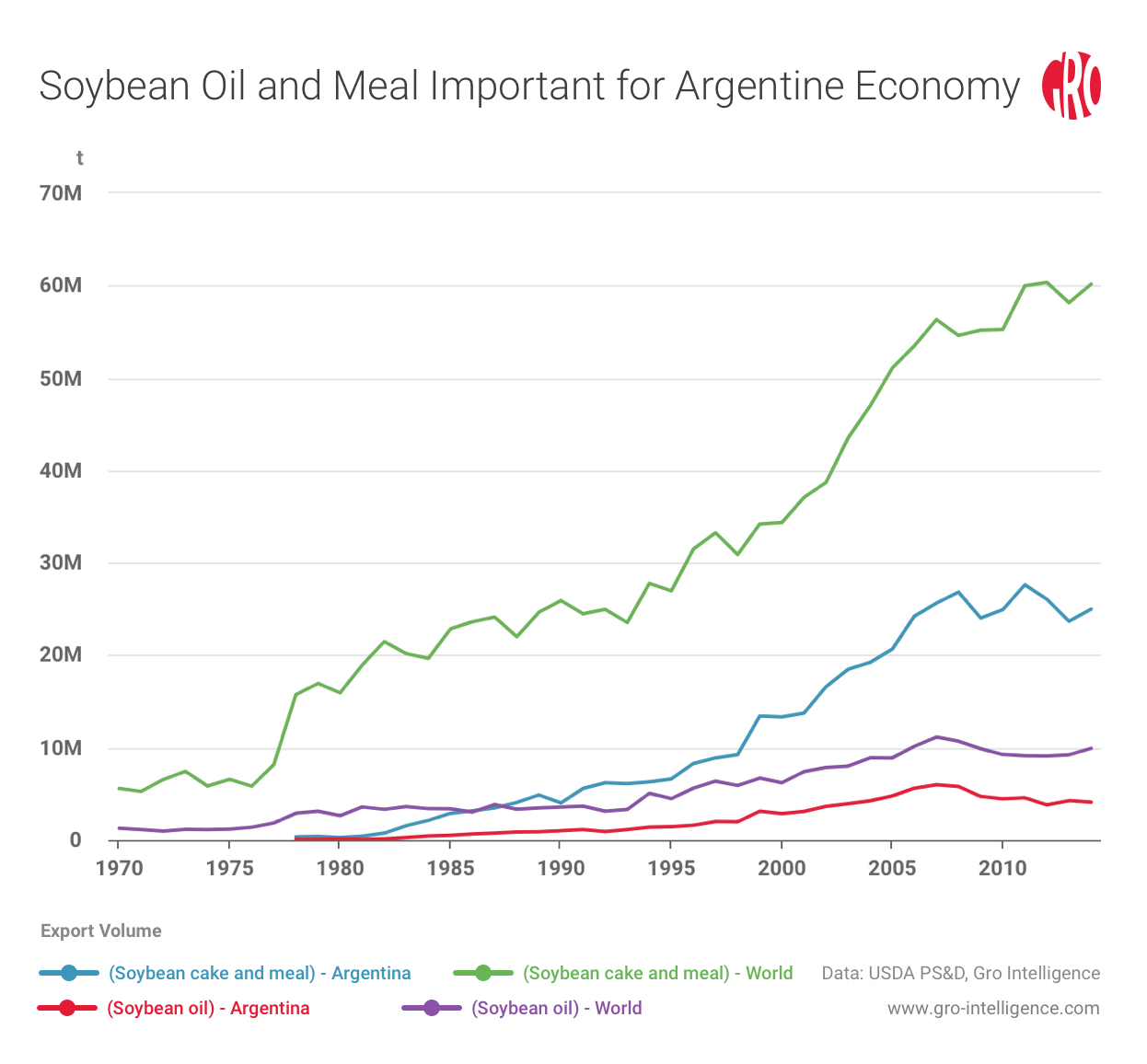

Argentina is the world’s third largest producer of soybeans after the US and Brazil, producing 53.5 million tonnes of the oilseed in the 2013/14 crop season, or more than 18 percent of the world total. Almost all of this production is geared toward the export market. Generally, the country exports 20 percent of its soybeans unprocessed and then processes the remainder into oils and meals, of which 93 percent and 99 percent are exported, respectively.

This makes Argentina by far the world’s largest exporter of both soybean oil and soybean meal. In 2013/14, the country exported almost 4.1 million tonnes of soybean oil (44 percent of total global trade), and 25 million tonnes of soymeal (41 percent of total global trade). The combined export sales of soybeans, soybean oil, and soybean meal totaled more than $19 billion in 2014. The previous year, these exports accounted for 26 percent of the country’s total exports and were Argentina’s primary source of foreign currency.

Argentina has allowed the use of approved biotech crop varieties since 1996, making the country one of the earliest adopters of the technology. From 1996 to 2011, GM technologies resulted in $72.6 billion in economic benefits and created 1.8 million jobs for the country. The distribution of these economic benefits within the soybean industry largely stayed within the country, with farmers collecting 72.4 percent of the total, the government 21.2 percent, and seed and herbicide suppliers just 6.2 percent.

While several trends seem to confirm Argentina’s embracing of biotech crops, several others send very different signals.

Monsanto in Argentina

Monsanto has been the focus of several environmental protests in Argentina, including a months-long blockade by activists on the proposed site of a Monsanto plant in Córdoba which halted construction. And while such protests and their associated delays do present a challenge to the company, the main thorn in Monsanto’s side has been the inability to collect royalties in Argentina.

Monsanto has had difficulty collecting what it sees as just remuneration for the company’s GM seeds for almost as long as Argentine farmers have used the technology. A key component of Monsanto’s revenue model is charging a technology fee on the output from farmers who use the company’s seed. This has been easy to do in the US where IP laws prevent farmers from reusing patented seeds, but the company has found this much more challenging in Argentina.

When Monsanto launched its first generation of Roundup Ready (RR) soybeans in 1996—a trait that enables seeds to resist Monsanto’s glyphosate herbicide, Roundup—it did so without an Argentine patent on the product. The absence of patent protection hindered Monsanto’s ability to control the distribution of their biotech products, but so did an Argentine seed law from 1973 which gave farmers the right to cull seeds from one harvest and use them again for the next. This law, written more than two decades before the introduction of GM crops, was originally designed to protect small-farmers, but much of Argentina’s soybean production is now done on a massive commercial scale. By 2010, when more than 18 million hectares of soybeans were harvested, just three percent of producers controlled greater than 50 percent of all cultivation.

The 1973 law gave farmers the ability to keep seed from harvest for the next crop, without ever having to go back to a grain dealer. While farmers were not technically allowed to sell their saved grain to other farmers, the practice became commonplace. And because one and a half bags of authorized seed could yield three tonnes of soybeans and 60 bags of new seed, unauthorized seed production spread quickly. By 2004, it was estimated that only 20 percent of soybean seeds on the market were sold by authorized dealers, 30 percent were collected by seed saving, and 50 percent came from seeds sold illegally on the black market. Some critics even speculate that Monsanto intended for seed to spread in this manner so that their technology would dominate and the demand for the herbicide Roundup would rise.

An important technical aspect to note about soybeans generally—not just biotech varieties—is that the plants are self-pollinating. This means that the seeds purchased from authorized dealers can be reproduced and reused in subsequent years without a significant reduction in yield. A farmer, therefore, has no need to buy fresh seeds from Monsanto or any other company after the original purchase. This is not true for some other crops like corn, as corn seeds are hybrids which result from the cross-pollination of at least two different corn plants. Corn farmers therefore need to buy new seed every year, as saved seeds will have dramatically reduced yield potential.

In January 2004, Monsanto ended all sales of and investments in Roundup Ready soybeans in Argentina. Company officials explained that they were no longer able to cover costs, and could only resume sales if provided protections from the government. Some analysts estimated that Monsanto’s Argentine revenues declined from $580 million in 2001 to $300 million in 2002.

In order to recoup some of these losses Monsanto tried, starting from 2006, to collect royalties on shipments of soybeans and soybean products being exported out of Argentina. Argentine law prevented Monsanto from collecting royalties within the country, but Monsanto held a patent for its product in Europe and attempted to prevent shipments of products containing the patented gene from entering the European Union (EU). In 2010, the EU’s highest court sided with Argentina’s argument that the patent only applied when the gene was used to protect plants from Roundup, not to products derived from soybeans with that genetic trait. Monsanto therefore had to focus just on selling the herbicide to Argentina’s soybean growers.

Round 2 for Roundup

Monsanto was not ready to give up on the potential profits to be made in the Argentine soybean industry and designed a new and improved seed to sell to farmers. The second time around, however, the company was sure to take many more steps to ensure that their right to collect royalties was protected. The first step in the process was designing a new seed which would be superior enough to the first generation of RR soybeans that farmers would want to buy it. Monsanto began working on the new and improved seed, now known as Intacta RR2 Pro, around 2002. The variety was specifically designed for South American growing conditions and offers several advantages to the original RR seed. The new Intacta seeds, which entered the Argentine market in mid-2013, maintain a resistance to the Roundup herbicide but also have a higher potential yield: test harvests indicated 12.5 percent higher yields than the original RR soybeans. The new variety also offers protection against soybean-attacking insects such as the velvetbean caterpillar, soybean looper, soybean bud-borer, lesser cornstalk borer, and corn earworm.

An analysis by Morgan Stanley estimated that Intacta seeds would provide an extra $60-$80 of value per acre, depending on commodity prices, prevalence of insects, and exchange rates. The extra value is derived from increases in yield, but the insect-repelling properties of Intacta mean that crops require less spraying, saving farmers money on insecticide, diesel fuel, and machinery costs.

With a superior product ready, Monsanto focused efforts on legally protecting its intellectual property. The company received an Argentine patent for the genetic traits of Intacta, but in an attempt to make their claims to royalties more ironclad, they started signing contracts with farmers in which the farmers committed to paying royalties if they were to acquire Intacta seed. Monsanto began signing these contracts in 2011, the year after losing their EU legal case.

The contracts, which did not require farmers to buy seed, were largely focused on guaranteeing the payment of royalties. If a farmer were to grow Intacta seed—which could be acquired through licensed third parties—they agreed to pay a royalty for every tonne of soybean that they delivered to a mill or exporter. Farmers could decide when to pay the price of the royalties, and the further in advance royalties were paid, the less it would cost the farmer. The price of the royalty ranged from $5.40 to $15 per tonne for the 2015/16 harvest year, and the current price of free on board (FOB) soybeans in Argentina is $360 per tonne.

Another requirement of the licensing agreement is a commitment from producers to reserve at least 20 percent of their harvest area for soybean varieties that do not contain the Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) gene—the gene which affords protection from pests. This 20 percent “haven” or “refuge” is designed to allow enough space for insects which are susceptible to the Intacta technology to survive so that they can breed with Bt-resistant insects and thus dilute the genetic success of resistant bugs. This practice would encourage persistently high yields, and also help bolster the value of Intacta seeds.

Despite the patent and the contracts—through which more than 70 percent of growers paid their royalty in advance—and agreements with grain handlers and ports in northern Argentina to collect royalties, Monsanto still faced collection resistance. Shortly after export companies began inspecting shipments for undeclared Intacta technology in April 2015, the government of Argentina, supported by the country’s largest farmers’ association, planned another ban on Monsanto’s ability to collect royalties. An official claimed the government was in favor of farmers paying for biotech, but that despite patents and contracts, Argentine law does not allow royalties to be charged on future outputs.

To uphold the seed law, but to assuage Monsanto and encourage biotech investment, Argentina’s Agriculture Ministry has begun devising a registry which will track how much biotech soybeans farmers sow in an attempt to prevent illegal seed resales. Farmers will be required to declare how much seed they replant and how much they set aside. Monsanto would still be denied royalties on farmers’ repeated use of their biotechnology, which the company says denies them a return on investment.

Perhaps in an attempt to offset these losses and to prevent seed manufacturers from getting discouraged from entering the Argentine market, the ministry also announced the creation of a fund that would help “finance the development of biotechnology in the country.” The fund would be developed from contributions from Argentina’s largest producers, but details on how these contributions will be collected, or whether any of this money will go to Monsanto have not yet been revealed.

Conclusion

The government of Argentina has made it clear they will not allow royalties to be charged on the future output of any crop, but recognizes the benefit of biotech seeds and wants to encourage the development and use of such technology. But it is unlikely that these two stances will be able to coexist forever.

Biotech seeds have contributed massively to creating what is now Argentina’s multi-billion dollar soybean industry. And if Morgan Stanley’s estimates of Intacta’s value addition of $60 per acre are correct, then the net value added of the variety to Argentina’s soybean industry could reach $2.37 billion per annum. But it is hard to imagine Monsanto, or any other biotech seed company, would be eager to commit to developing and releasing a new product within Argentina if returns on those investments are constrained by Argentine law.

Biotech companies spend huge amounts of money on research and development—Monsanto claims the company invests more than $2.6 million per day.

And if Argentina proves to be an unfavorable biotech environment, then those funds may be diverted elsewhere.

With soybeans, some Argentine farmers may be able to piggyback on technology introduced in Brazil, as biotech seeds introduced there would likely be smuggled across the border—just as Monsanto worried would happen with Intacta if that technology was introduced in Brazil before protections were in place in Argentina. But relying on smuggled seed is not the best method for industry growth.

Funding for biotech research and development could be a welcome compromise between supporting small farmers and encouraging technological growth, but details on how funding will be structured remain unclear. Argentina will need to make some accommodations to make biotech companies feel secure in investing in future products for the country.

The long-term picture, however, is much more complicated. The costs of gene sequencing and DNA manipulation will only continue to fall as the technology they require becomes more prevalent. Not only that, but some industry analysts predict that the ongoing open-source revolution will eventually engulf the development process of GM seeds. Essentially, the biotechnology sector is on the verge of revolution. In the coming years and decades, therefore, the current Argentina-Monsanto dispute may disappear without ever reaching a conclusion.

Blog

BlogSouth America: Fall Planting Snapshot

Insight

InsightSoggy Start to Spring Points to Fertilizer Application Delays for US Corn

Insight

InsightChina’s Grain Imports Reach Record With a Growing Reliance on Brazil

Insight

Insight

Search

Search