Vietnam’s Open Borders Expose an Inefficient Sugar Industry

A Porous Barrier

Prior to 2018, Vietnam maintained a sugar TRQ for ASEAN countries. The quota, or cap, was set at 89,500 tonnes annually, per a World Trade Organization (WTO) agreement. For an ASEAN member, Vietnam taxed sugar imports at five percent until they imported 89,500 tonnes total from that country in a year. Once that annual cap was achieved, the tax increased to 80 percent for any additional sugar imports from that country. Nations outside the trade bloc face rates of 25 percent and 40 percent for in-quota raw and refined sugar, respectively. Most of Vietnam’s sugar imports are from fellow ASEAN member Thailand.

As part of the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA), Vietnam agreed to remove both the import cap and sugar import tariff by 2018. The Vietnam Sugarcane and Sugar Association (VSSA) advocated maintaining a five percent tariff on imported ASEAN sugar to avoid a deluge of foreign sugar into Vietnam. Although their concession was met, legal sugar imports should be the least of Vietnam’s concerns.

Raw and refined contraband sugar has been flooding into Vietnam from Thailand for the last few years. Vietnamese sugar executives estimate between 300,000 and 500,000 tonnes of Thai sugar illegally enters Vietnam each year. Some even suspect that the bootlegged volume rose to 700,000 tonnes in 2017. Excluding the European Union (EU), Thailand became the third largest global sugar producer in 2016. Sources disagree on the amount of legal sugar imports in Vietnam, but all reported values have risen in aggregate since 2004. While removing the cap may simply redirect some smuggling to legal avenues, the Vietnamese government must nevertheless focus on plugging the holes in its border.

Inefficiency of Vietnamese Sugar

Vietnamese sugarcane farmers are already at a disadvantage. In 2016, producer prices for sugarcane were $44.70 per tonne in Vietnam compared with $20.90 per tonne in Thailand. In February 2018, the price of Thai and Vietnamese sugarcane were approximately $30 per tonne and $50 per tonne, respectively. Vietnamese sugar yields also sit well below those of the top producers in East Asia and Oceania, further highlighting the industry’s internal inefficiencies.

The inefficiency continues up the supply chain, as most sugar refineries in Vietnam are too small to capture scale economies. The smaller Vietnamese sugar plants process approximately 2,500 tonnes a day, about half the rate of an average Thai sugar refinery. There are 40 Vietnamese sugar plants, which can handle about 155,000 tonnes of sugarcane per day, while Thailand holds 51 factories capable of processing about 245,000 tonnes of sugarcane daily.

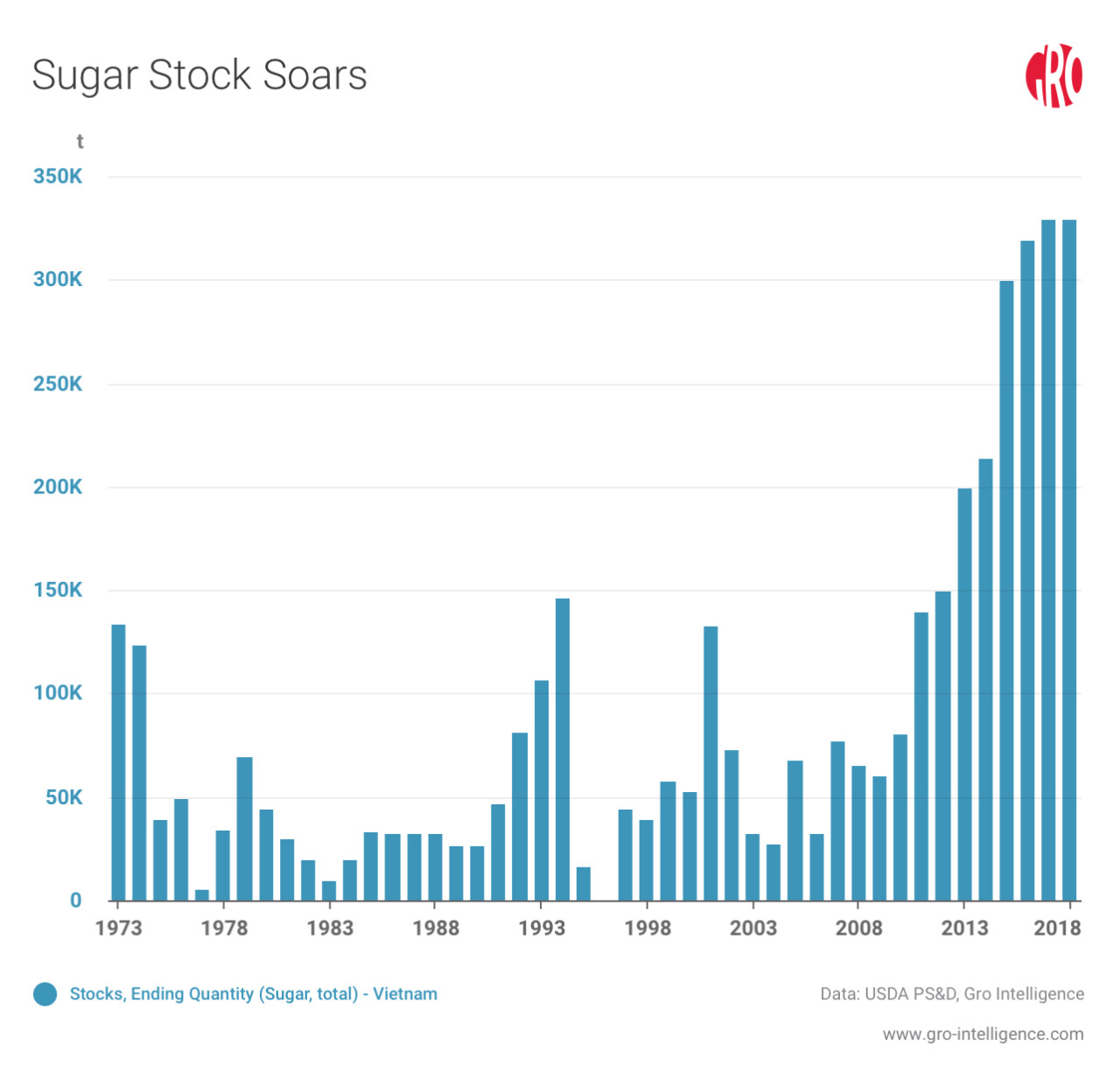

These layers of inefficiency force the Vietnamese sugar price to consistently run above the global average. Smuggled Thai sugar is often one third cheaper than Vietnam’s domestic sugar, leaving Vietnamese refineries unable to sell their product. As a result, Vietnam’s sugar stock has increased annually since 2009. The stock grew to 330,000 tonnes in 2017 from 61,000 tonnes in 2009, with the VSSA estimating a stock of 388,000 tonnes in early March of 2018.

Sugarcane Goes Sour

This year, Vietnamese refineries are turning away farmers’ sugarcane due to oversupply. The local government warned farmers in the Tra Vinh province not to harvest their entire sugarcane crop, because the nearby processing plant was at capacity. Without a destination, farmers are leaving sugarcane unharvested or are taking on additional costs by transporting the crop to further districts. Producers throughout the Mekong Delta, where a majority of Vietnamese sugarcane is produced, could face up to a 40 percent loss on the 2017/18 crop.

As the losses add up, farmers are reportedly planning to convert acreage to fruits, vegetables, or even aquaculture. Sugarcane planted area had remained relatively consistent in Vietnam up to now. Each year between 2000 and 2016, Vietnamese farmers planted an average of 290,000 sugarcane hectares. The standard deviation was only 17,000 hectares, or six percent of the mean.

The Shift from Sugar

Between the TRQ removal, producer inefficiency, and Thai sugar smuggling, the contraction of the Vietnamese sugar industry appears inevitable. Industry participants project just 15 of the 40 Vietnamese sugar plants will remain open in 2025. However, the sugar industry’s decline may be partially mitigated by the 2 million jobs Vietnam added from 2015 to 2017. The World Bank projects significant economic growth for Vietnam over the next 20 years.

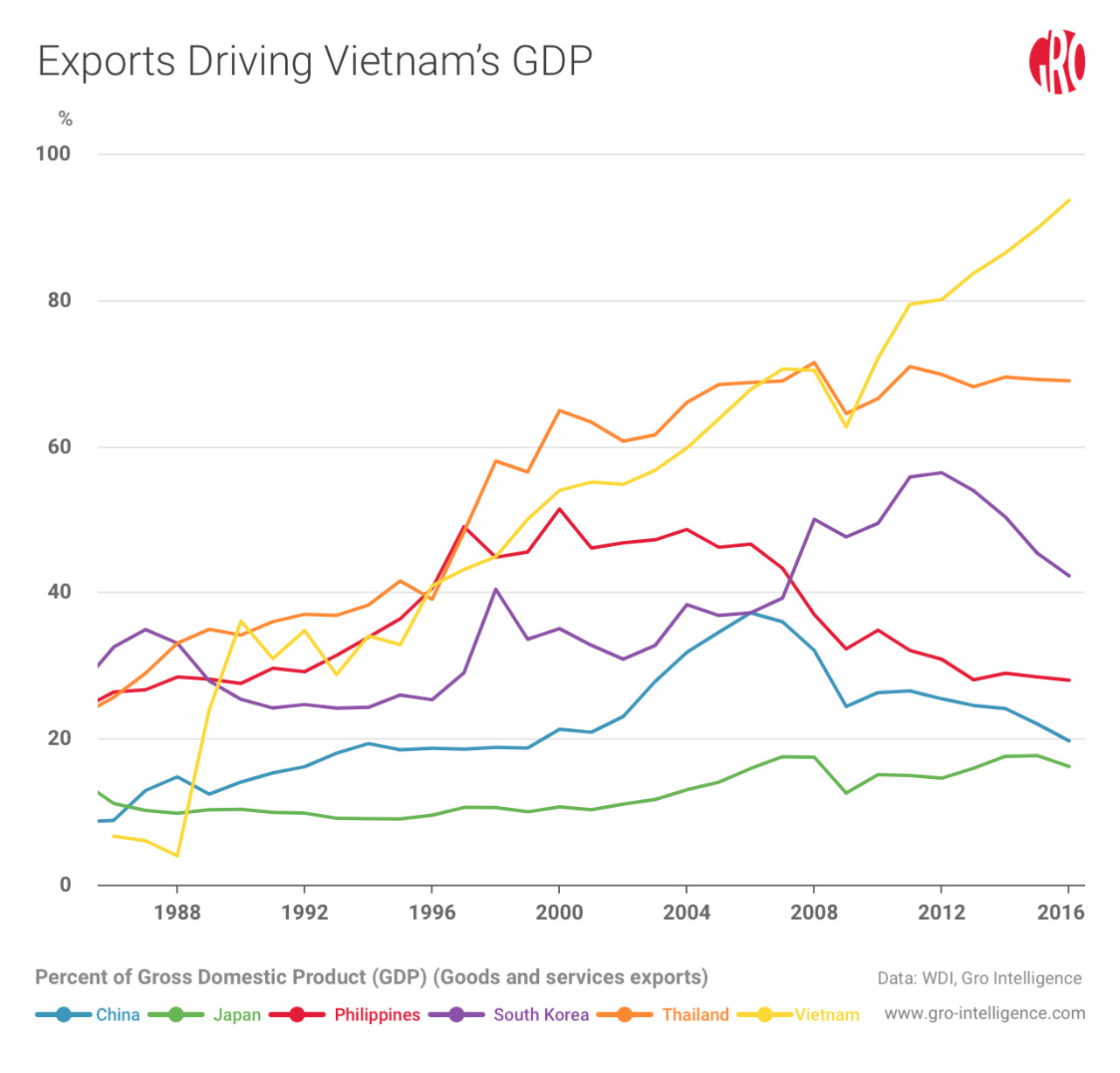

Under the most conservative estimate, the World Bank predicts The Comprehensive and Progressive Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) alone will increase Vietnam’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 1.1 percent by 2030. Vietnamese exports of goods and services have quickly become the foundation of the economy, accounting for 94 percent of the country’s GDP in 2016.

Between ATIGA and CPTPP, Vietnamese sugarcane farmers and sugar plant workers can shift into expanding billion-dollar markets like coffee, crustaceans, and nuts.

Despite the contraction, the Vietnamese government must still focus on two areas to support the surviving competitive pieces of the industry. First, Vietnam can fashion deals like the recent one between the Vietnamese division of Coca-Cola and VSSA. The agreement guarantees that 100 percent of the sugar purchased by the Coca-Cola branch will be domestic. Coca-Cola will also increase extension work to train Vietnamese farmers and improve sugarcane production. However, the efforts behind Coca-Cola’s investment in Vietnamese sugar will prove to be futile if illegal sugar continues to undermine domestic sales. Thus, the Vietnamese government must also tighten its borders to assure farmers and refineries can more easily sell their goods at their respective local markets.

Even with rampant sugar smuggling, inefficiency has led to contraction in Vietnam’s sugar industry. The transition will undoubtedly cause short term stress for some as farmers reallocate land to other crops. The economic future of Vietnam looks sweet, but sugar will play a sharply diminishing role.

Insight

InsightPoor French Sugar Beet Crop Adds to Global Sugar Inventory Woes

Insight

InsightIndia’s Sugar Crop on Track for Another Strong Year

Insight

InsightRice Crops Face Risks From Higher Fertilizer Prices

Insight

Insight

Search

Search